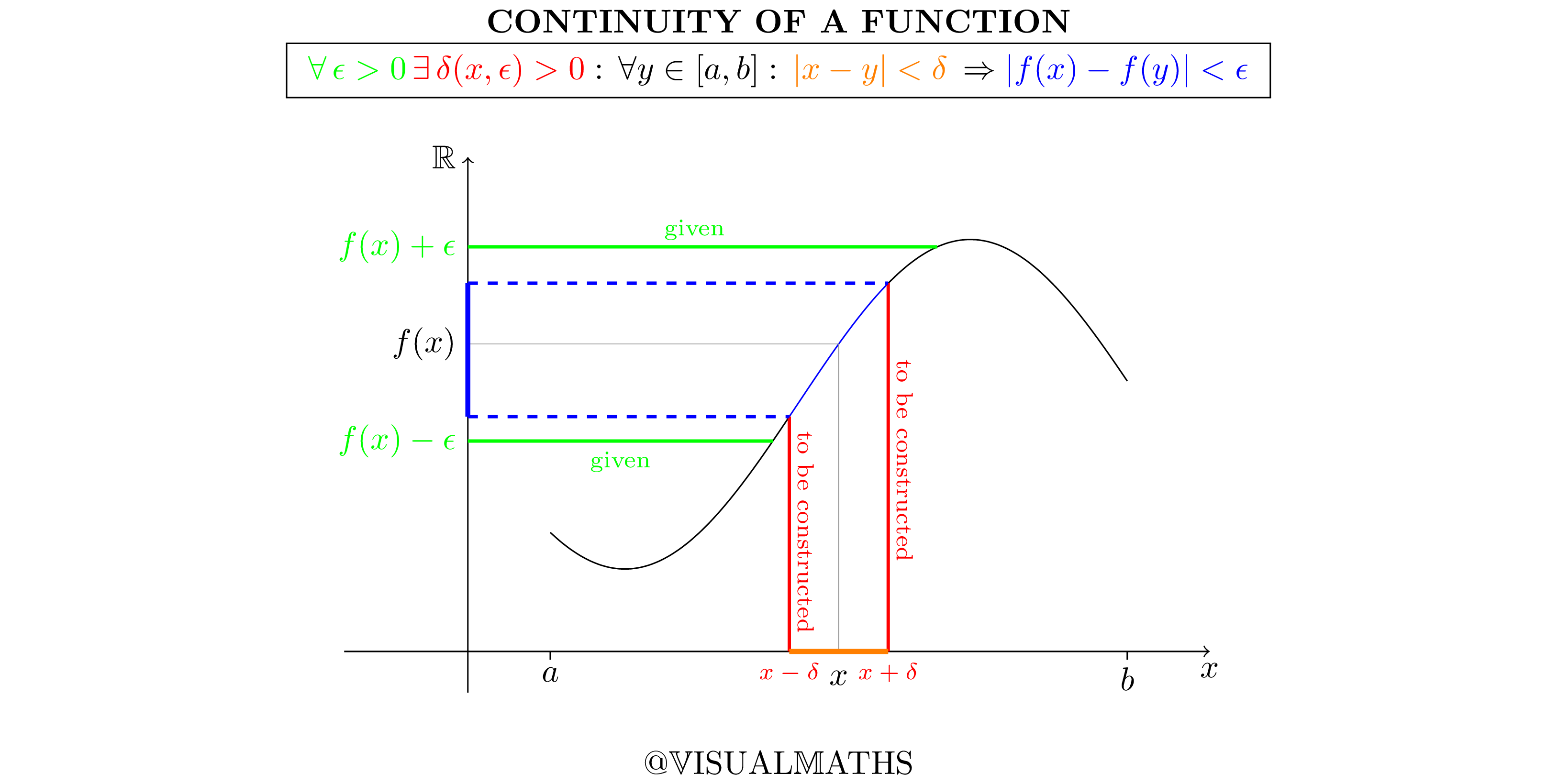

In this first post, I want to focus on a very important definition of real analysis: the continuity of a function. I want to combine both, the formal –

-definition and a possible visualization of what’s going on and what needs to be done, when showing that a function

is continuous at a point

. So let’s have a look at the formal definition and a picture that visualizes the statement.

Let’s repeat the formal definition of continuity at a point :

So, what is going on here? Roughly speaking, this definition says that small neighbourhoods around get mapped to small neighbourhoods of

. But let’s have a closer look. Without going too deep into predicate logic, it is important to notice that the order of quantors is essential. The first part is that for all (which means, arbitrarily given)

there exists a

. So, what do we need to do? A statement that has to hold for all means, that we cannot put any restrictions on that element. Precise: when proving continuity, we need to whish ourselves an arbitrarily chosen

, no matter how small or how big it is (see the region enclosed by

and

on the

-axis). From this arbitrary choice, the following existence quantor

leads to the next step: we have to show existence! But how do we do that when all we have for the moment is our function

, the point

and our arbitrary

which doesn’t provide any information? Showing existence means constructing the required element. Precise: we have to construct the

from the point

and

. Note that

in general depends on

and

. Before studying how to construct

, let’s go further into the definition. The next part says that all we have done so far has to hold for all

, that is less far apart than

away from

(see the orange region in the picture). So, again: to prove this, we have to chose

arbitrarily. From this, we have to show an implication. This means, that we may assume that

and our arbitrarily chosen

lie less than our constructed

away from each other. From this assumption we need to show that our constructed

is indeed sufficient to prove

(see the blue region on the

-axis). And that’s basically it. But: how do we construct

? That’s the tricky part when proving continuity from the definition is the construction because one has to have clever ideas regarding the manipulation of the expression

. We know by assuming that

, so what can we do to make this expression appear in

? Yes, try to manipulate until we can estimate by

, because then we can apply our assumption. Precise:

You may ask yourself: why may not depend on

? The answer is that the existence of

in the definition is predicted before saying that the foregoing has to hold for all

.

Let’s have a look at a concrete example: the continuity of .

Let be given. We want to show that this function is continuous at any

. Before writing out the formal proof, we have to think about how to get

into play, starting with

. Notice that the

that we are going to choose may only depend on

and

. So, let’s try to make a clever estimate:

Fine, so we made it to bring the expression into play. The problem is that the rest not only depends on

, but also on

(remember:

may not depend on

). The good news is that we are free to choose any

, as long as we can conclude

. So, let’s make an assumption: let

. From the reversed triangle inequality we know that

. This is great, since we are now in a position to make an estimate on

in terms of

. So, let’s go ahead and try to make an estimate on

:

Looks good. We’ve made an estimate that does not depend on and we can now see what our delta has to look like. In order to make the last expression less than

, simply take the smaller choice of the two that we made:

. Now we can wrtite out the formal proof of

being continuous at

:

Let be arbitrarily given. Choose

. Further, let

be arbitrary and assume

. To show that this choice of

implies

, we make the following estimate:

This completes the proof.